All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Prevalence and Factors Associated with Acute Postoperative Pain after Emergency Abdominal Surgery

Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to assess the prevalence and associated factors of acute postoperative pain after emergency abdominal surgery in the first 24 postoperative hours among adult patients.

Methods:

An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted on adult patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital from March 1 to May 30, 2020. Data were collected by delivering questionnaires through interviews and reviewing the patients’ charts. Data were entered into Epi Info software, version 7.2, and analyzed by SPSS version 20. Logistic regression was applied to point out independent risk factors for postoperative acute pain. Variables with a p-value of < 0.05 were taken as significant.

Results:

165 patients participated in the study with a response rate of 98.2%. Among these, 75.8% [95% CI: (69.8%, 82.3%)] of patients experienced moderate to severe acute postoperative pain. Female gender [AOR:3.9, 95%CI: (1.22,12.5)], preoperative anxiety[AOR:4.4,95%CI:(1.74,11.1)],moderate to severe preoperative pain[AOR:5.79,95%CI:(2.08,16.1)], and incision length ≥10cms [AOR: 4.86, 95%(CI:1.88,12.5)], were significantly associated with moderate to severe acute postoperative pain.

Conclusions and Recommendations:

The prevalence of immediate postoperative pain following emergency abdominal surgery was found to be high in this study. Acute postoperative pain was substantially linked to the female sex, preoperative anxiety, preoperative pain, and an incision length of ≥10 cm. The prevalence of moderate-to-severe acute postoperative pain as well as the factors that contribute to it can be used to develop particular preventive strategies to reduce patient suffering.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience related to actual or potential tissue damage.

Postoperative pain is the most common symptom encountered by hospitalized surgical patients. It is caused by the actual tissue damage with the release of chemical mediators from the abdominal incision wound. This pain may cause shallow breathing, atelectasis, retention of secretions, patient dissatisfaction, prolonged opioid use, the development of chronic postoperative pain, and increased medical costs. This increases the prevalence of postoperative morbidity and leads to delayed recovery [1, 2].

Acute postoperative pain after abdominal surgery can be a significant problem because it has been shown to alter the metabolic response, resulting in a delayed recovery with a longer stay and increased morbidity, as well as the development of a chronic pain state through the 'wind up' process and central sensitization [3, 4].

Within the first 24–48 hours after abdominal surgery, the prevalence of postoperative pain varies between studies. The proportion of patients experiencing moderate to severe pain 24 hours after abdominal surgery ranged from 22 to 67 percent [5-7]. According to studies conducted in developing nations, a significant rate of postoperative pain and poor postoperative management was seen [4, 8].

The most common predictors of severe pain reported include female sex, young age, preoperative severe pain, anxiety risks and problems, drug type and route of administration, type and duration of surgery, postoperative pain treatment, previous pain experiences, smoking, American Society of Anesthesiologist status, chronic pain, marital status, socioeconomic status, educational status, and surgical history [9-11].

Self-report is the most accurate form of pain assessment, and the numerical rating scale has strong sensitivity, validity, and reliability for pain assessment, as well as being widely validated across a variety of patient types [12, 13].

Experts recommend a thorough evaluation of patients and the use of multimodal strategies such as preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative interventions; systemic analgesics; intrathecal administration of opioids; use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; and various neuraxial and peripheral blocks as part of effective post-operative pain management [14, 15].

Studies on the incidence and factors associated with pain after emergency abdominal surgery are relatively scarce in Ethiopia. Hence, this study aimed to explore patients' experiences of pain and associated factors after emergency abdominal surgery. It will provide insight into patients' experiences of pain immediately after emergency abdominal surgery and pave the way for effective pain control, decreased hospital stay, and decreased cost of early discharge.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design, Period, and Area

An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted from March 1 to May 30, 2020. The study was conducted at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit and in the surgical ward. The University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital is one of the greatest and most well-known hospitals in Ethiopia. It serves more than 5 million people as a referral for the district and other hospitals.

2.2. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

2.2.1. Sample size

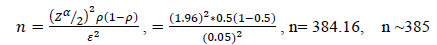

Since there is no study done in Ethiopia on the prevalence and associated risk factors of acute postoperative pain after emergency abdominal surgery, a single population proportion formula was used, and the sample size was calculated by taking the proportion of 50%, assuming a 95% confidence interval with a 5% margin of error, and finally, the sample size is calculated as:-

|

Since the total number of emergency abdominal surgeries in our hospital annually is below 10,000, a correction factor formula was used to get the exact sample size. In the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, according to the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health, University of Gondar Hospital operation room register book and record review, an average of 91 emergency abdominal operations were done in the main operation theatre per month [16]. Therefore the total sample size within the data collection period will be calculated as follows:

, Where: nF=Adjusted sample size, n= Initial sample size N=Population size, nF =

, Where: nF=Adjusted sample size, n= Initial sample size N=Population size, nF =

, nF= 159.75, nF~160

, nF= 159.75, nF~160

When a 5% of nonresponse rate was added, the total number of patients who participated in the study was 168.

2.3. Data Collection Tools and Procedures

After taking written consent from each patient to participate in the study, the patient’s socio-demographic data (age, sex, weight, Body Mass Index, religion, and ethnicity), ASA status, and type of procedure were recorded. Two data collectors were selected from among BSc anesthetists, and training was given before data collection. The data collection procedure included a chart review and an interview-based questionnaire. From the chart review, preoperative condition, intraoperative status, analgesic medications, and postoperative conditions were assessed and recorded. In the interview, participants were asked for the required data. The supervisor controlled the data quality and its completeness at the end of data collection for a single participant. The data collectors took informed consent, reviewed the chart, and documented the pain severity at rest and with movement by using NRS at 2, 12, and 24 hours postoperatively. At the same time, the analgesics were also documented. Data collections were done based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3.1. Questionnaire

A pretested and semi-structured questionnaire containing the numeric rating scale was used for assessing and measuring postoperative pain. The NRS was taken with 3 measurements in the first 24 hours of the postoperative period; 2 hours since the end of surgery and the return of full consciousness, the second on the 12th hour, and the third on the 24th hour. The patient’s ward and bed number were documented on the questionnaire before they left the recovery room and were followed to their respective wards for the 2nd and 3rd pain scores.

2.4. Study Variables

2.4.1. Dependent Variable

Prevalence and associated factors of acute postoperative pain after emergency abdominal surgery.

2.4.2. Dependent Variable

Independent variables

2.4.2.2. Preoperative Factors

Preoperative anxiety, preoperative analgesics, ASA status, preoperative pain, previous experience of operation, and sleeping disorder.

2.5. Data Quality Assurance

To ensure the quality of data, the pretest of the data collection was done on 5% of the samples of the patients who had undergone emergency abdominal surgery, which was not included in the main study, and the questionnaire was modified appropriately. The collected data were checked for completeness, accuracy, and clarity.

2.5.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

All general surgical patients with the age of ≥18 and ASA classification of I-III underwent emergency abdominal surgery.

2.5.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients who have documented and newly diagnosed cognitive dysfunction and ongoing treatment of chronic pain, and patients who are unable to self-report pain.

2.6. Data processing and analysis

The collected data were checked manually for completeness and entered into Epi-info software version 7.2 and then exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20 computer program for analysis. Multicollinearity between independent variables was checked and there was no correlation (P>0.5). The association between independent factors and the outcome variable was determined by the chi-square test and bivariable and multivariable logistic regression. Crude and adjusted odds ratios were used to see the strength of the association for bivariable and multivariable logistic regression, respectively. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

A total of 165 emergency abdominal surgical patients were recruited in the analysis with a 98.2% response rate. Three patients were excluded due to incomplete data because of missing measurement time points for pain scores. Age, sex, BMI, marital status, and level of education were assessed in this character. Males accounted for 115(69.7%) and females were 50(30.3%). The mean age ± Standard Deviation and mean BMI±SD of the participants were 34.69±14.97 and 21.39±2.62, respectively (Table 1).

3.2. Preoperative Factors

For preoperative factors, greater numbers of respondents were kept on ASA I & II; 133 (80.6%). More than half reported moderate to severe preoperative pain; 84 (50.9%) and 102 (61.8%) reported preoperative anxiety (Table 2).

| Variables | Category | Frequency(N) | Percentage (%) |

| Sex | Male | 115 | 69.7 |

| Female | 50 | 30.3 | |

| Age | 18-39 | 104 | 63.0 |

| 40-59 | 45 | 27.3 | |

| ≥60 | 16 | 9.7 | |

| BMI | <18.5 | 20 | 12.1 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 137 | 83 | |

| 25-29.9 | 7 | 4.2 | |

| ≥30 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Educational status | Illiterate | 47 | 28.5 |

| Can read and write | 27 | 16.4 | |

| Primary school(1-8) | 37 | 22.4 | |

| Secondary school(9-12) | 28 | 17.0 | |

| College and above | 26 | 15.8 |

| Variable & Category | Frequency(N) | Percentage (%) | Post-operative pain in 24 hours | ||

| None-mild (N, %) | Moderate-severe (N, %) | ||||

| ASA- status | |||||

| I & II | 133 | 80.6 | 34(20.6%) | 99(60.0%) | |

| III | 32 | 19.4 | 6(3.6%) | 26(15.8%) | |

| Preoperative analgesics given | |||||

| Yes | 47 | 28.5 | 24(14.5%) | 23(13.9%) | |

| No | 118 | 71.5 | 16(9.7%) | 102(61.8%) | |

| Type of analgesics at the preoperative time | |||||

| Tramadol | 20 | 12.1 | 11(6.7%) | 9(5.5%) | |

| Diclofenac | 18 | 10.9 | 9(5.5%) | 9(5.5%) | |

| Paracetamol | 8 | 4.8 | 3(1.8%) | 5(3.0%) | |

| Diclofenac+PCM | 1 | 0.6 | 1(0.6%) | 0(0.0%) | |

| Not given | 118 | 71.5 | 16(9.7%) | 102(61.8%) | |

| Preoperative pain | |||||

| Yes | 84 | 50.9 | 7(4.2%) | 77(46.7%) | |

| No | 81 | 49.1 | 33(20.0%) | 48(29.1%) | |

3.3. Intra-operative and Postoperative Factors

From the intraoperative factor distribution, a large proportion of patients, 93(56.4%), had undergone laparotomy and 66(40%) had undergone appendectomy, and 91(55.2%) of patients had an incision length of ≥10cm (Table 3).

| Variables | Frequency(N) | Percentage (%) | Postoperative pain within 24 hours | |

| None-mild N (%) | Moderate-Severe N (%) | |||

| Surgery Type | ||||

| Laparatomy | 93 | 56.4 | 16(9.7%) | 50(30.3%) |

| Appendectomy | 66 | 40 | 22(13.3%) | 71(43.0%) |

| Cholecystectomy | 6 | 3.6 | 2(1.2%) | 4(2.4%) |

| Anesthesia Time (in Minutes) | ||||

| <60 | 2 | 1.2 | 1(0.6%) | 2(1.2%) |

| 60-180 | 142 | 86.1 | 36(21.8%) | 105(63.6%) |

| >180 | 21 | 12.7 | 3(1.8%) | 18(10.9%) |

| Nerve Block Done | ||||

| Yes | 23 | 13.9 | 8(4.8%) | 15(9.1%) |

| No | 142 | 86.1 | 32(19.4%) | 110(66.7%) |

| Type of Nerve Block | ||||

| TAP | 9 | 5.5 | 2(1.2%) | 7(4.2%) |

| Infiltration | 7 | 4.2 | 2(1.2%) | 5(3.0%) |

| Rectus sheath | 1 | .6 | 1(0.6%) | 0(0.0%) |

| Rectus sheath+TAP | 5 | 3.0 | 2(1.2%) | 3(1.8%) |

| Paravertebral | 1 | .6 | 1(0.6%) | 0(0.0%) |

| Note done | 142 | 86.1 | 32(19.4%) | 110(66.7%) |

| Anesthesia Induction | ||||

| Ketamine | 132 | 80.0 | 33(20.0%) | 99(60.0%) |

| Propofol | 7 | 4.2 | 3(1.8%) | 4(2.4%) |

| Ketofol | 26 | 15.8 | 4(2.4%) | 22(13.3%) |

| Postoperative Analgesics Given | ||||

| Yes | 113 | 68.5 | 30(26.5%) | 83(73.4%) |

| No | 52 | 31.5 | 28(44.2%) | 35(67.3%) |

| Type of Postoperative Analgesics | ||||

| Tramadol | 59 | 35.8 | 18(10.9%) | 41(24.8%) |

| Diclofenac | 24 | 14.5 | 4(2.4%) | 20(12.1%) |

| Diclofenac+tramadol | 9 | 5.5 | 5(3.0%) | 4(2.4%) |

| Fentanyl | 18 | 10.9 | 3(1.8%) | 15(9.1%) |

| Morphine | 3 | 1.8 | 0(0.0%) | 3(1.8%) |

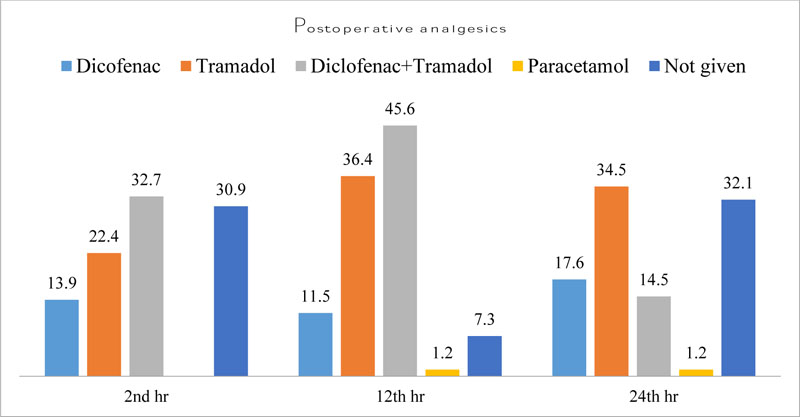

3.4. Analgesics Were Given Postoperatively

Participants were given different types of systemic analgesia at different time gaps for the management of acute postoperative pain after emergency abdominal surgery. For that systemic analgesia, the combination of diclofenac and tramadol was frequently given (32.7%) and (45.6%) at the 2nd and 12th hours, respectively. Whereas, 30.9% and 32.1% of the participants did not take any systemic analgesia in the 2nd and 24th hours, respectively. Tramadol is given frequently in 36.4% and 34.5% in the 12th and 24th hours, respectively (Fig. 1).

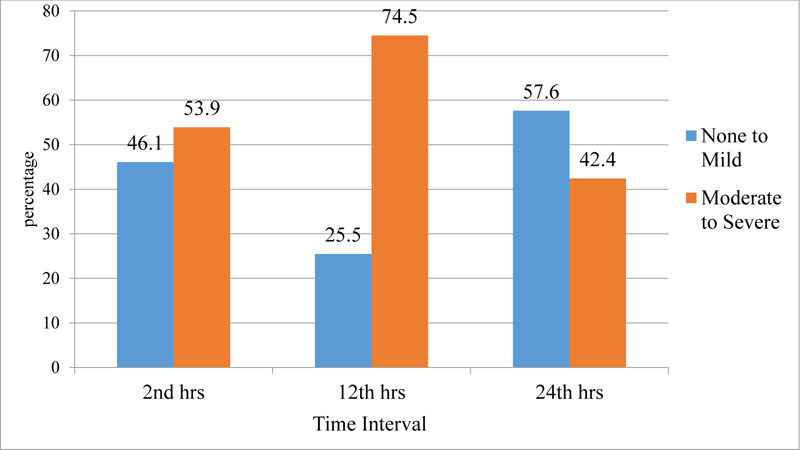

3.5. Post-operative Pain Prevalence

At the 2nd postoperative hour, 89 (53.9%) of the participants reported moderate to severe pain, while 76 (46.1%) reported no to mild pain. At the 12th postoperative hour, most of the participants (123) reported moderate to severe pain. In the last 24 hours postoperatively, 70 (42.4%) of the participants experienced moderate to severe pain. Of the 113 patients who were given analgesics, 30 (26.5%) experienced non– mild pain and 83 (73.4%) experienced severe pain. Of the 52 patients who did not receive analgesics, 28 (44.2%) experienced non–mild pain and 35 (67.3%) had severe pain. Therefore, in this study, the overall prevalence of acute postoperative pain at 24 hours was 75.8% [95% CI: (69.8%, 82.3%)] with the numerical rating scale of the pain assessment method (Fig. 2).

3.6. Factors Associated with the Prevalence of Acute Postoperative Pain within 24 Hours

We analyzed the variables in both bivariable and multivariable logistic regression methods to control potential confounding factors and to determine the independent association between postoperative pain and factors of acute pain. With the bivariable analysis method, sex, age, preoperative pain, preoperative analgesics, preoperative anxiety, and incision length were significant with a P-value < 0.2 (Table 4).

On multivariable logistic regression analysis, the following variables were found to have moderate to severe pain in post-abdominal surgery; compared with males, females were 3.93 times more likely to have acute postoperative pain [AOR:3.93,95%CI:(1.22,12.5)]. Accordingly, participants who had anxiety in the preoperative period were 4.41 times more likely to have moderate to severe postoperative pain than those who were not anxious [AOR: 4.41, 95%CI:(1.74, 11.1)]. Similarly, the odds of having moderate to severe postoperative pain were 5.79 times [AOR: 5.79, 95%CI: (2.08, 16.1)] higher among participants who had moderate to severe preoperative pain than those participants who had no moderate to severe preoperative pain. The study also revealed that an incision length of ≥10 cm was 4.86 times [AOR: 4.86, 95%CI: (1.88, 12.5)] more likely to have moderate to severe acute postoperative pain compared to participants who had an incision length of <10cm (Table 4).

| Variables & Category | Postoperative pain within 24 hours | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

| None-mild N (%) | Moderate-Severe N (%) | Crude (95% CI) | Adjusted (95%CI) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 34(20.6%) | 81(49.1%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 6(3.6%) | 44(26.7%) | 3.078(1.2,7.89)* | 3.93(1.22,12.5)** |

| Age in Years | ||||

| 18-39 | 20(12.1%) | 84(50.9%) | 2.52 (0.81,7.75)* | 1.58(6.88,0.36) |

| 40-59 | 14(8.5%) | 31(18.8%) | 1.32 (0.40,4.37)* | 0.80(0.14,4.37) |

| ≥60 | 6(3.6) | 10(6.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Preoperative Pain | ||||

| No | 33(20.0%) | 48(29.1%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 7(4.2%) | 77(46.7%) | 7.56(3.1,18.4)* | 5.79(2.08,16.1)** |

| Preoperative Analgesics | ||||

| Yes | 24(14.5%) | 23(13.9%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 16(9.7%) | 102(61.8%) | 1.63(0.78,3.39) * | 1.26(0.48,3.29) |

| Preoperative Anxiety | ||||

| No | 28(17.0%) | 35(21.2%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 12(7.3%) | 90(54.5%) | 6(2.748,13.10)* | 4.41(1.74,11.1)** |

| Incision Length in Centimeters | ||||

| <10 | 30(18.2%) | 44(26.7%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥10 | 10(6.1%) | 81(49.1%) | 5.5(2.47,12.34)* | 4.86(1.88,12.5)** |

**=Variables significant in the multivariable logistic regression analysis (p<0.05), N=Number

1.00=Reference/indicator.

4. DISCUSSION

Based on these findings, the overall prevalence of moderate to severe acute postoperative pain after emergency abdominal surgery was 75.8% [95% CI:(69.8%, 82.3%)]. This finding was consistent with the study conducted in South Africa, which was 79% [17] and a study in Iran, Kerman’s teaching hospital, which was 78.3% [18], and a study conducted in Queensland, Australia, which was 73.5% [19]. Our result was also supported by a study done in the USA, which showed that more than 80% of patients complain of pain during the postoperative period, with 75% rating it as moderate, severe, or extreme [20].

However, this finding was lower than a study conducted in Jimma, Ethiopia, which reported that moderate-severe pain was 88.2% [21] and a cohort study in Danish patients, which reported 83.3% after gastrointestinal surgeries [22]. This disparity could be related to insufficient pain treatment, such as when present, analgesia is insufficient to relieve pain for long periods or when breakthrough pain is not properly managed.

This result was also higher than that of two earlier studies done in Kenya, one of which had a 48% result and the other had a 56.2% result [23, 24]. A study conducted in Iran showed 62% [25] result and a study in Turkey found 68.9% result [26]. This difference may result from the use of preoperative counselling, multimodal analgesia, and sufficient epidural analgesia for pain control. This result was also higher than a study conducted in Spain, which ranged from 22 to 67% [6] and in the Netherlands, which ranged from 30–55% [14]. This discrepancy might be due to adequate pain assessment, documentation, and management of pain with different analgesic modalities.

Females were 3.93 times more likely than males to experience moderate to severe acute postoperative pain, according to several studies. This finding was consistent with the study conducted in Germany and the USA [27-29]. Females were experiencing moderate to severe postoperative pain compared to males. The reason for this might be due to the fact that females are at greater risk of experiencing many forms of clinical pain and are more sensitive to experimentally induced pain than males. Compared to females, males exhibited less negative pain responses when focusing on the sensory component of pain [30-32].

The study demonstrates a relationship between preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain prevalence. Those participants who had anxiety in the preoperative period were 4.4 times more likely to have moderate to severe postoperative pain compared to those who were not anxious. This finding was supported by a study done in Brazil, which revealed that patients who were anxious in the preoperative period had moderate to severe postoperative pain as compared to non-anxious patients. This might be due to the reason that psychological characteristics like anxiety and fear of pain predict postsurgical pain and have been shown to be significantly associated with postoperative pain after abdominal surgery, and an anxious state has been advocated as a factor in lowering pain threshold, facilitating overestimation of pain intensity [33]. Psychological distress, such as preoperative anxiety, has a negative effect and can increase postoperative analgesic consumption. Normally, the mild level of preoperative anxiety has not been identified or recognized as having critical repercussions, especially in patients without a psychiatric diagnosis [11, 34]. According to this study, patients who had moderate to severe pain preoperatively had moderate to severe acute postoperative pain compared to those who did not. This conclusion was supported by research conducted in Brazil and Canada [11, 35]. This might be due to patients with pain prior to surgery displaying increased sensitization to peripheral nociceptors and exaggerated sensory pain input through the release of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandin E2 and nerve growth factor and opioid-induced hyperalgesia [36-38]. Pain perception may also be influenced indirectly when patients expect to recover from surgery and return to daily routines with little inference from pain, and negative emotional states following surgery may be less apparent and less likely to exacerbate pain intensity [39, 40].

An incision length of ≥ 10cms was 4.86 times more likely to have acute postoperative pain compared to an incision length of <10cms. This result was supported by a study done in Ethiopia and in the Netherlands [41, 42]. Skin incision-related processes lead to inflammation and sensitization of the peripheral and central neurons, thus accelerating a concomitant neurophysiologic stress response that will increase postoperative pain [43].

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The preoperative poor documentation system gave analgesics on the chart; this means the documentation may not be appropriate on the patient's chart even when the drug was given.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The prevalence of immediate postoperative pain following emergency abdominal surgery was found to be high in this study. Acute postoperative pain was substantially linked to the female sex, preoperative anxiety, preoperative pain, and an incision length of

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ASA | = American Society of Anesthesiology |

| BMI | = Body Mass Index |

| CI | = Confidence Interval |

| NRS | = Numerical Rating Scale |

| RCT | = Randomized Control Trial |

| UoGCSH | = University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital |

| AOR | = Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| NSAIDs | = Non-Steroidal Anti -Inflammatory Drugs |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| USA | = United States of America |

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is, in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of the School of Medicine, University of Gondar. An official permission letter was obtained from the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital administrator, to conduct research. The purpose and benefit of the study were explained to the patients.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used that are the basis of the study. All human procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines of the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki 1964.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was taken from all study subjects to secure the confidentiality of patient information.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

STROBE guidelines were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

This published article contains all data generated or analyzed during this study.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors’ deepest gratitude goes to the University of Gondar, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, for helping them conduct this research. The authors also appreciate their data collectors for their enthusiastic and energetic participation in the process of data gathering. Finally, the authors extend their gratitude to the study participants who spent their precious time responding to their questionnaires.